Last night, 8:32 p.m. CT. A truncated transcript from a call (note: I’m sensitive to using a single anecdote to make decisions, but this was teachable moment):

(me): “Hello”

(some guy, about 10 second later): “Hello? Um, hello?”

(me): “What can I do for you?”

(some guy): “Is Mr. or Mrs. Cannon home?”

(me): “This is Chris Cannon?”

(some guy): “This is [name] calling for [top 10 national nonprofit]. I’m not calling to raise money. [really?] I’m calling to ask you to write10-15 letters…[script went on for another minute]”

(me): “Thanks. That’s not really how we like to participate in the organizations we suppo…”

(some guy): Click.

Seriously? I answered the phone, listened to some guy, and was interested enough in the organization to start to tell him how I might become engaged and that guy hung up. The reminder here is that we entrust dozens, maybe hundreds of people to our philanthropic brand each day. Are you doing all you can to train, engage, and otherwise prepare these folks to be good stewards of your good will? Are callers on quotas that diminish real discussions? If you’re not addressing these issues, your fundraising may suffer along with your brand.

The phone call didn’t provide the only lesson, though. After hang-ups, etc., I frequently call the organization back. I care a lot about nonprofits, and I’d bet management would like to know when their good reputation is being sullied.

So, in calling this organization back, an odd and maybe very dubious thing happened. The 800 line provided an opt-out (“press 2 if you do not want to receive calls like this”). I pressed “2”. Then, I had an option to add my number to the organization’s opt-out list. Terrific, I thought. I didn’t want more wasted calls like the one I had just experienced. Next, though, a very curious thing happened. I entered my phone number but the computer program didn’t register it correctly. I entered my area code but the computer-generated response indicated a different number. My wife watched me enter the correct number, only to hear the wrong number repeated back. I hung up and called back with similar results. I tried a third time and the computer program finally “figured” it out. Computer programs can fail, of course, but it sure felt like a purposeful, nearly endless loop to get off the list.

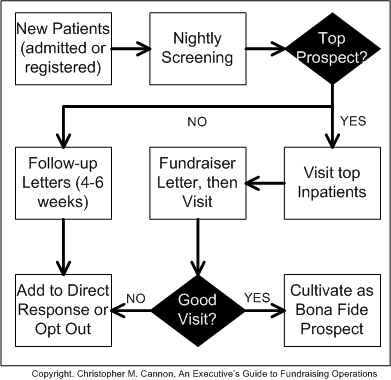

So, the second lesson of such a call is that, even if it’s an error or an oversight, you can lose potential donors forever by appearing to be too automated, too computer-driven, and too focused on your agenda rather than your potential donors. Fundraising is my vocation and I encourage groups to push their boundaries. For example, I frequently tell healthcare nonprofits that it’s patently irresponsible not to engage patients as potential donors. I do so because it can raise dollars and I truly believe in the power of philanthropy in the healing process (see a great application from Children’s Minnesota). This advice isn’t about limiting efforts but your strategy should mirror your constituency and stay away from gimmicks.

I’d love to hear your stories about these sorts of experiences. Together, we can help to keep our reputations strong and our (potential) donors happy.