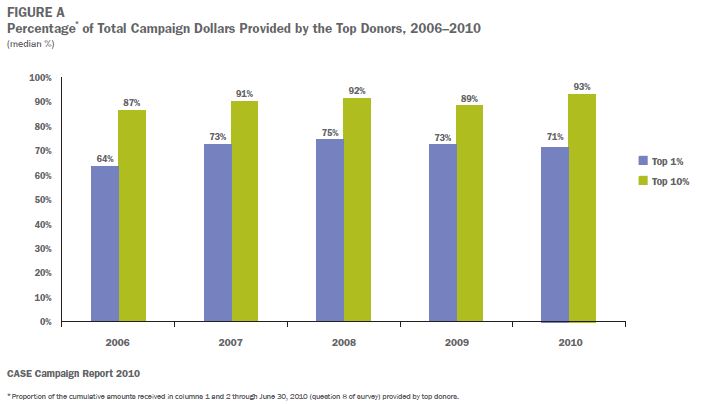

Most of us have heard of the Pareto Principle, or the 80-20 rule (80% of production comes from 20% of the resources). For years, philanthropy experts have used this economics principle from Vilfredo Pareto to explain why so much giving comes from so few people.

Of course, for many of the “best” fundraising organizations, that ratio is more like 99-1. That is, in many cases, single, sometimes 9-figure gifts dramatically shift the fundraising landscape for an organization. These great gifts are frequently transformative and non-repeatable, making the replacement of such big gifts a driving and often maddening force for fundraisers. And, such huge gifts may have the unintended consequence of diminishing future, smaller donations from others whose future in the 1% is yet-to-be-determined.

How should you deal with your organization’s experiences with this rule? Here are two angles of approach.

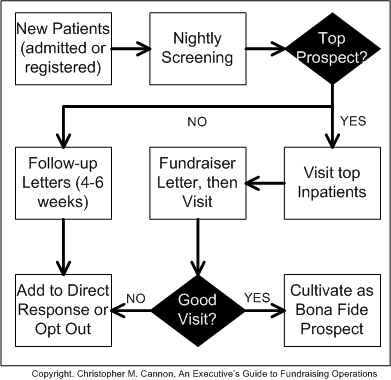

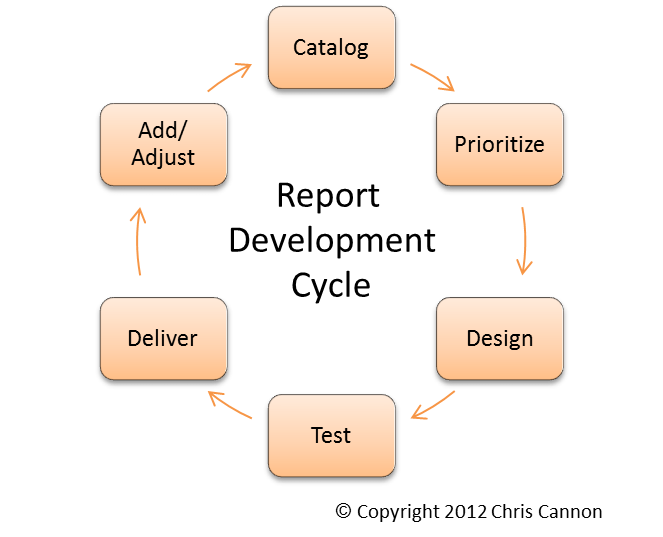

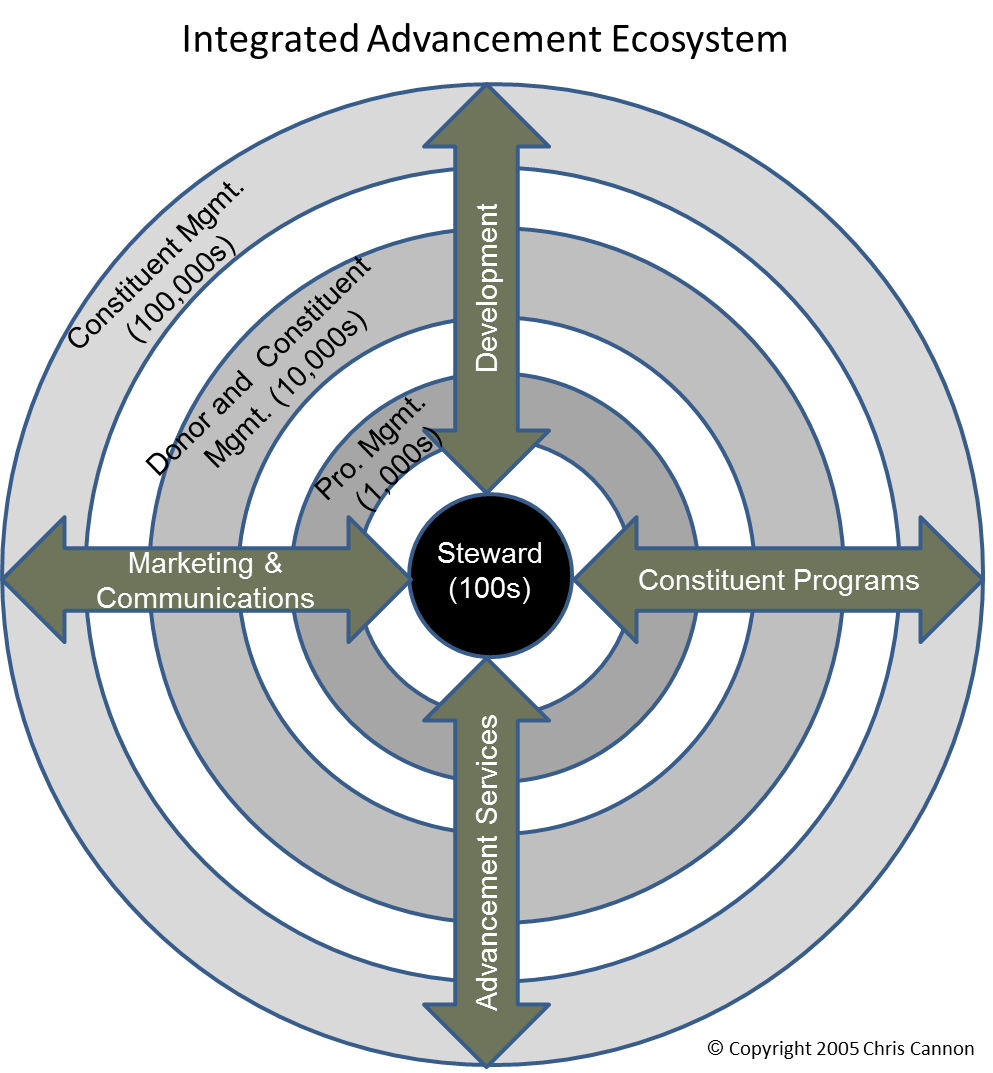

First, your team (researchers, analytics folks, prospect management professionals, gift officers, etc.) need to know wealth, and particularly your organization’s profile. How is it generated? Who has it? Who had it? Who can get more of it, so big gifts are reasonable? Who has so much that they’d like to leave a legacy instead of being the richest guy in the graveyard. A great set of articles in the NY Times (click here) puts some perspective on how new wealth is being generated. Your team needs to know these trends, your constituent’s sources of wealth, and stay on top of it.

Second, and slightly related to the other 99-1 “Occupy” messaging so prevalent in 2011, your team needs to understand that the enormous gap between the super-rich and the rest of us has big ramifications for your programs and your mission. Sure, we need to devote more time to our best prospects. But, you cannot just focus on the super-rich, because it’s a fluid and sometimes cloaked group. And, for many nonprofits, mass-effort, grassroots fundraising pays the bills, even if less efficiently than 7- and 8-figure gifts seem to. So, your team should work hard to treat all constituents well, while employing effective annual giving, analytics and other tactics to maintain base building efforts that help the best bubble to the top.

So, our fundraising efforts need to efficiently direct energy toward the 1% while conscientiously engaging the 99% as valuable near-term partners, some of whom may matriculate into the 1% (or are already there!).

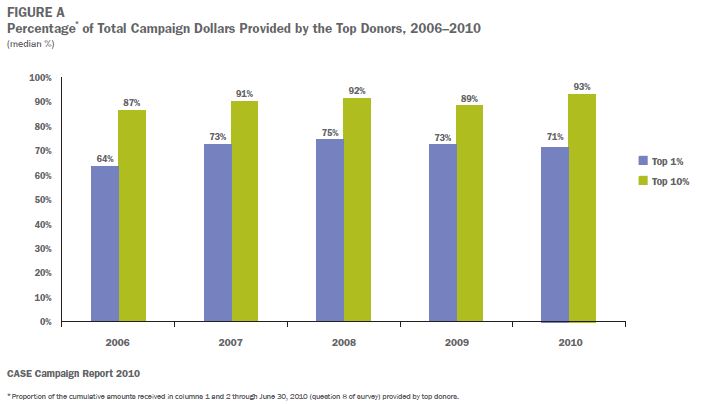

UPDATE: CASE provided some great data on this topic. Here you can see the impact of the top few percent of donors on campaigns. It appears this is a little more like the 70:1 rule, but the lessons are the same: